“You cannot kill ideas with bullets, that’s the most barbarian response,” says cartoonist Felipe Galindo, known by his artist name, Feggo. But that’s exactly what terrorists tried to do on January 7, when they charged into the offices of satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo in Paris, shooting and killing 12 people — two police officers and 10 staffers.

Among the victims was Georges Wolinski, one of France’s best-known cartoonists and the man who led the founding team at Charlie Hebdo (then called Hara-Kiri) as editor-in-chief from 1971 to 1980, until it folded. When it re-launched in 1992, Wolinski was part of the team that resurrected it.

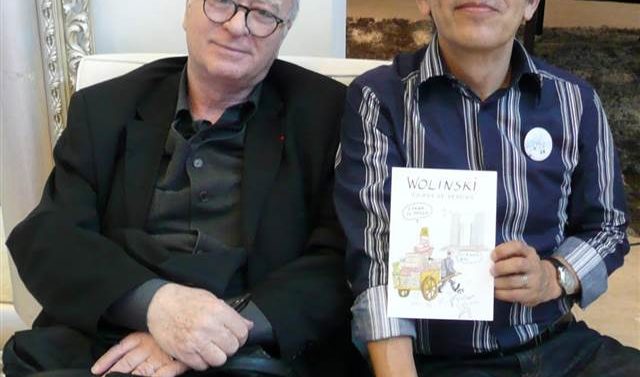

For Feggo, 57, Wolinski was someone to admire. “I knew his name and cartoons since the 1970’s but had never seen a photo of him,” he says.

Feggo wouldn’t meet Wolinski until June 2012 at the Porto Cartoon Festival in Portugal, where the Mexico-born, New York City-based artist won an award for this cartoon on global warming, originally published in Reader’s Digest.

Wolinski, whom Feggo describes as “a very gentle and quiet man, very different from his outrageous and satirical cartoons,” was among the jurors who selected Feggo as the winner among 2,500 entries.

“He is the one who handed me my award and diploma,” recalls Feggo, “we had the opportunity to spent time together in many events for a few days, from breakfast at the hotel to a boat cruise with the president of Portugal.”

Wolinski was 78 at the time, and what struck Feggo about the artist was not only how different he seemed in person from his cartoons, but also how open he was to other types of humor.

“He not only was looking at the world through his humor but recognized other types of expressions that spread across a message in a different manner,” says Feggo. He and his wife Andrea Arroyo, also an artist, had just returned from Paris when they heard the news of the Charlie Hebdo massacre and have each created an homage to Charlie Hebdo in the wake of the shooting.

Despite the tragedy, Feggo says he feels hopeful for the future of satire.

“Many more ideas and creators will spring out of the fallen ones,” says Feggo. “The killings created the opposite of what the terrorists wanted, instead of silencing, the cartoonists’ images spread worldwide like a chain reaction. The solidarity has been enormous, even if people didn’t agree with their kind of humor.”

Here, Feggo remembers his friend and comrade, the loss of whom he continues to mourn.

Did Wolinski ever express remorse/regret or fear as a result of the editorial direction at Charlie Hebdo?

He didn’t mention it and I don’t think the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo ever thought about remorse nor fear. They had been a target in 2011 and that didn’t deter them. They have been doing that kind of humor since the 1960’s before with Hara-Kiri magazine and later in their new incarnation as CH. They were the most critical and vociferous voice in cartooning in France. Always aiming at politics and politicians, religion, established powers, the ills of society, etc. When the religious extremists appear on the scene early in the XXI century and after they threaten to kill a Danish cartoonist portraying the Prophet in a series of cartoons, Charlie Hebdo began to criticize fundamentalists and their narrow and dangerous interpretation of Islam.

What do you interpret the mission of the slain Charlie Hebdo cartoonists to be and how does it align with yours?

Their goal was to use freedom of expression to the fullest. Some of their humor and cartoons can look very immature, grotesque or blasphemous, but it was well thought to get their message across. The cartoonist Charb’s famous quotes sums up their philosophy: “I don’t blame Muslims for not laughing at our drawings. I live under French law. I don’t live under Quranic law…I’d rather die standing than live on my knees.”

In my case, I don’t do this kind of humor; I prefer to make people laugh or reflect on an idea or concept through whimsical images. But I respect their right to exercise their freedom of thought and expression. I believe in making people think and question and debate ideas but in a different manner, not with bullets.

What makes French satire different, what sets it apart from everyone else’s?

French satire was, along with the English, the first in the world to criticize the power, being they kings, emperors, popes, politicians. The cartoons from the 18th century against the king and Napoleon were merciless. This team of cartoonists follow that centuries old tradition. But at the same time Charlie Hebdo was also a small publication of only 60 thousand copies, a “specialized” market. They were struggling financially because their magazine wasn’t for everybody. And now it is the most popular on the planet with a run of 5 million! It looks like the only people reading it before were those fanatics and were taking offense.

As a political cartoonist yourself, has there ever been a time when you held back or censored yourself and if so, what were the circumstances?

I sometimes hold back if I think I’m going to offend with my drawing, it’s my nature. I think there are many ways to say something with my drawings, and at the same time it creates a challenge for me on how to get my message across in a more subtle and humorous way.